YOUR BUSINESS AUTHORITY

Springfield, MO

YOUR BUSINESS AUTHORITY

Springfield, MO

Workforce training takes a lot of forms, but apprenticeship – in which a master craftsperson teaches aspects of their skill one on one over time – is the oldest by far.

Hammurabi’s Code, the law of ancient Babylon, required artisans to pass knowledge of their crafts to the next generation as a way of keeping those skills alive. A little over 30 centuries later, in the Middle Ages, craft guilds offered seven-year apprenticeships.

Today, when people think of how workers gain trade skills, they might picture a place like Ozarks Technical Community College, with over 100 courses of study from agriculture and auto repair to welding.

But in trade unions across the country, apprenticeships are still going strong, at least 51 centuries in.

The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 453 has its union hall on Division Street, just off U.S. Highway 65. Behind it is another building: the Jack F. Moore Training Center.

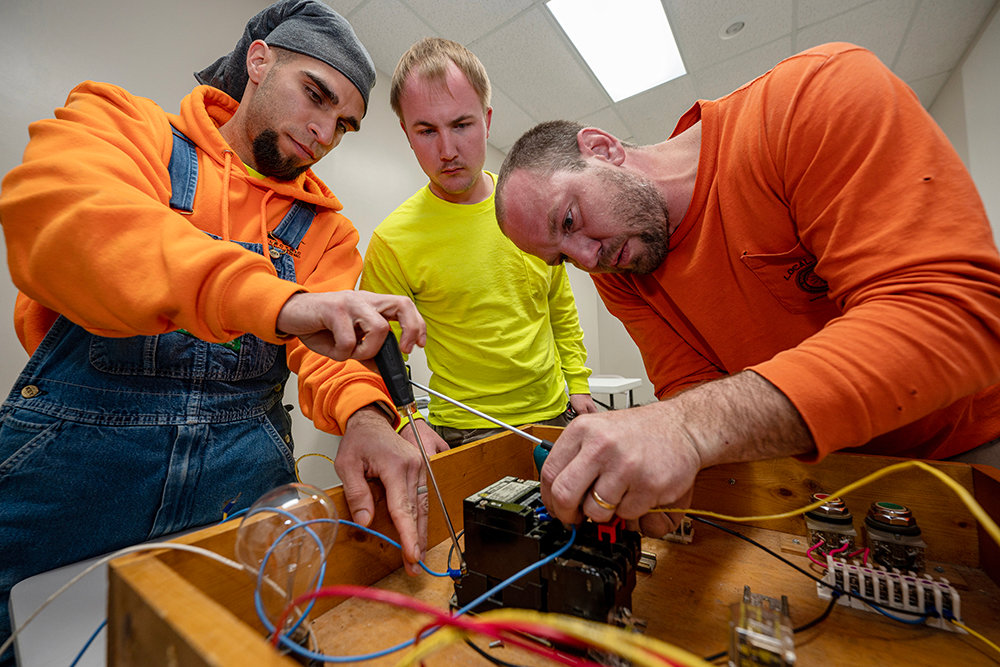

On a recent evening, five classes were in session. In one room, first-year students were being tested on the complex math that’s part of the electrical trade, while down the hall, fourth-year apprentices were assembling a circuit as a team while receiving prompts and coaching from their instructor, union President Scott Miller. In the back of the room, Ohm’s law is expressed mathematically on the wall. The formula is basic to the electrical trade; it states that the current through a conductor between two points is directly proportional to the voltage across the two points.

That seems to have something to do with not getting zapped, and it’s different than what apprentices might be learning at a plumbers and pipefitters hall.

“Plumbing, you might get wet. Electric can kill you,” a student jokes.

It seems there is some friendly competition among the trade unions, and apparently it starts early.

How apprenticeships work

IBEW Local 453 has some 70 apprentices among its 600 members. Kevin McGill, the union’s business representative, said the numbers are growing.

“We’ve been busy,” he said. “Over the last three years, we’ve grown by roughly 100 new members, and our apprenticeship has nearly doubled in size.”

While most training programs require students to pay for their education, McGill said that’s not the case with union apprenticeships.

“Our apprenticeship is tuition free; the only thing students pay for is their books,” he said.

In fact, apprentices earn pay and benefits as they learn, with pay rising as they advance toward journeyman status. Most apprentice programs have people enter the union on permit and become members after six months. They work alongside journeyman electricians – that is, professionals in the field who have completed apprenticeships.

McGill notes the U.S. Department of Labor-approved curriculum is rigorous and deep.

“There’s a difference between knowing how to do something and understanding,” McGill said. “Electricity is very complex. You can know how to hook up a light switch, receptacle, motor, transformer, whatever, but that doesn’t necessarily mean if something goes haywire that you would have the ability to figure out why.”

McGill said the apprenticeship starts with the theory of electricity, then works through the way transformers and motors work until it hits on all the aspects of the trade.

But one lesson is constantly reinforced.

“Safety is one of our biggest emphasis points,” McGill said. “Second to that is quality of work, and then everything else falls in line after that. If you do a high-level quality of work the first time around, you don’t have to go back and redo stuff. It saves time in the long run.”

Carpentry apprenticeship

Dan Montgomery is a business representative for Carpenters Union Local 978. The United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America has a half-million members nationwide. He, too, has been seeing membership grow.

“We’re definitely seeing our numbers rise,” he said. “In the last three to four years, even through COVID, I would say that our new member recruitment is up about 16%.”

Most of the new members join through apprenticeships.

“I think it’s indicative of mom and dad getting the message that there’s some real career options in various industries that do not have a prerequisite of traditional college,” he said.

Montgomery said he works through public school counselors to share information about the apprenticeship option for graduates. He said schools track where their graduates end up, and union apprenticeships are another option for students to consider.

“It’s very formal,” he said. “We consider it college for the trades.”

Apprentices are paired up with journeymen. While IBEW apprenticeships take classes nightly, carpenters attend classes quarterly, for one week four times a year. Montgomery said about 65% of their classes are accredited industry certifications for either technical or safety pathways.

Contractors like to use union professionals, according to Montgomery.

“Any company, union or not, they have to be able to prove that any person – like a laborer, carpenter or millwright – has had some kind of training,” he said. “That’s kind of where we win out as a labor organization.”

Montgomery said a lot of people hear about training programs like welding schools that they can finish in less than a year.

“When they graduate, they still need to find a job, but they only have one skill – they can weld,” he said.

A skill is not a trade, Montgomery said; rather, trades include multiple skills, and apprenticeships teach the trade comprehensively.

Montgomery said an apprentice graduates as a professional journeyman carpenter, and through an arrangement with OTC, they can earn an associate degree simultaneously.

Cindy Stephens, OTC’s director of technical education, said apprentices can either wait until they complete their journeyman license before coming to OTC or they can work on an associate degree concurrently with their union training.

“OTC recognizes the rigor of their apprenticeship training, so they don’t have to take those courses again,” she said.

She added that OTC also provides related instruction for companies that want to participate.

Apprentice view

IBEW apprentice Rico Berry said he was introduced to the career by a friend whose dad was in the union.

“Nobody talked to me about trades before that. I wish in high school someone would have told me that it was an option,” he said. “I had good grades, but I didn’t really aspire to go to college.”

Berry said he likes where he has landed, and he appreciates the security of his union membership.

Mike Malas said he is 40 years old and came to the apprenticeship program from a career in sales.

“I’m the grandpa apprentice,” he joked. “I’m one of the oldest guys in the apprenticeship.”

Malas said his father was a union electrician, and he knew he wanted to get out of sales, so he followed his example.

“It was not really a no-brainer, but I knew my dad was really good at what he did, and I know that there’s a real need for it. So, I entered the program,” he said.

McConnell Edwards markets hard-won expertise at answering tough questions.

Curb Appeal: April brings $19M in high-end home listings

Shawnee gunpowder company announces acquisition

Springfield Trading Co. set to open hot sauce shop

Buc-ee’s plans store in Kansas City area

Missouri man sentenced for PPP fraud

150th Kentucky Derby ends in photo finish

Lake of the Ozarks casino supporters submit 320K signatures for ballot